The Weird Limbo I

Strong thoughts and ideas in the first person about contemporary art creation, taken from the documentary “Time Stands Still”, directed by Artur Ribeiro in 2021.

By loading the video, you agree to Vimeo’s privacy policy.

Learn more

Watch the full documentary here .

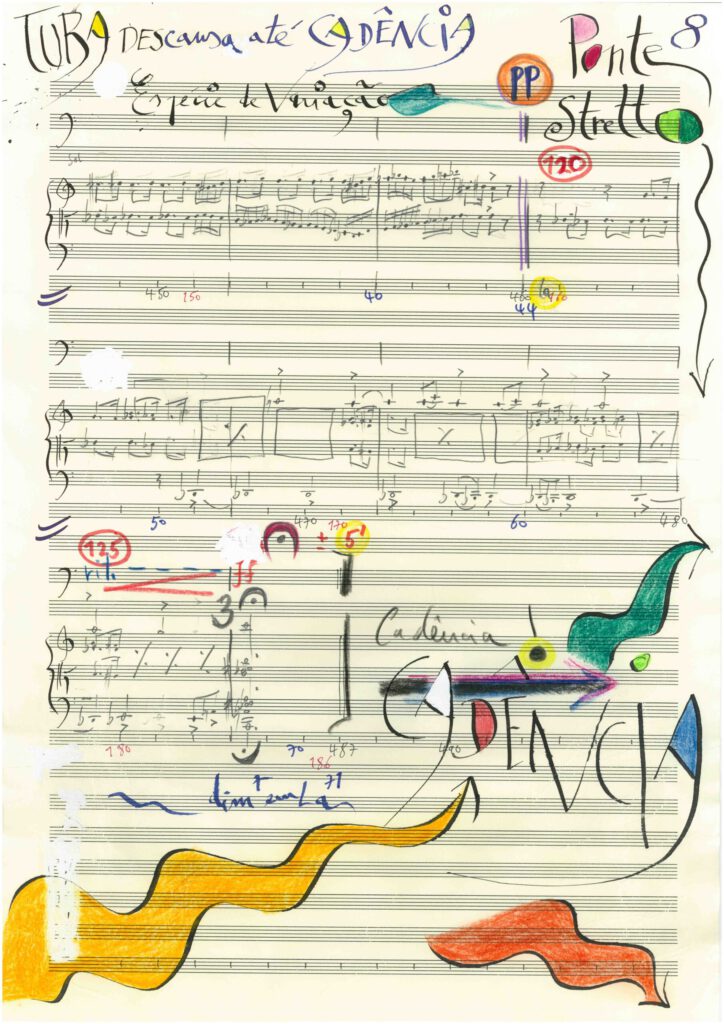

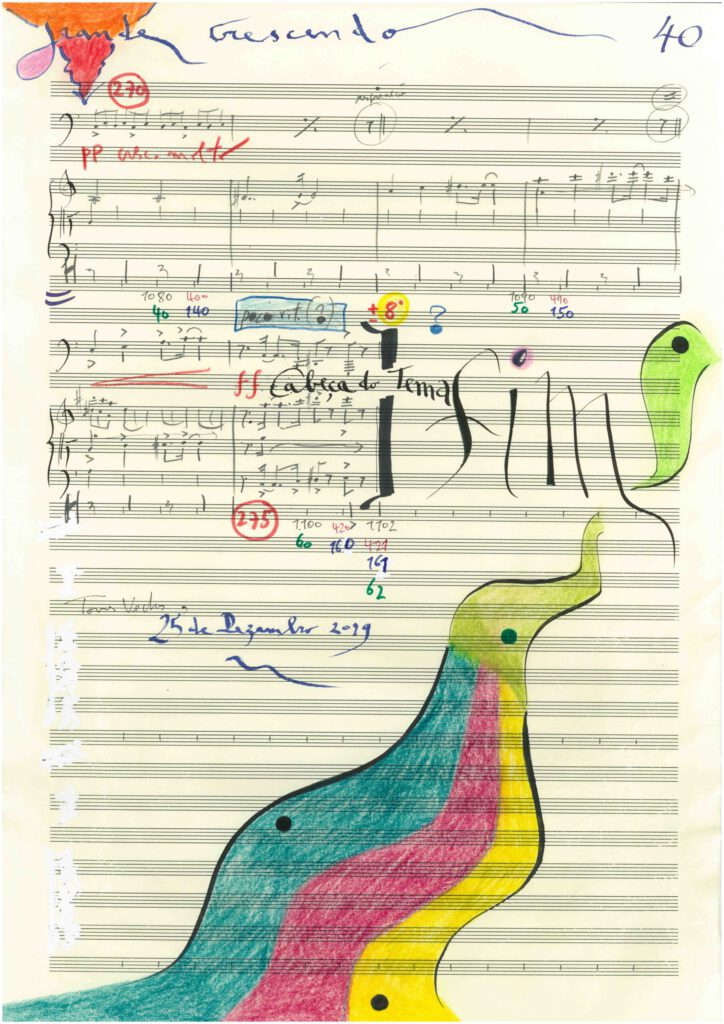

VISUAL MUSIC

For me, music has always been a handful of colored strokes on an imaginary canvas, evoking shapes, timbres and poetry, in a kind of magical arena where color and sound merge into poetic feelings. As a boy, I remember painting lying on the bedroom floor, to the sound of Beethoven’s symphonies, and then composing songs admiring Kandinsky’s colorful and miraculous abstract strokes! The act of creating has always inhabited this dichotomy, this magical relationship between music and painting, or, if one prefers, between music and visual arts; in a word: synesthesia. This is what truly moves my creative impetus, what makes me imagine sounds, foresee colors and idealize shapes, what inspires me to navigate into the undefined world of Art. In each new composition I begin, I spend long hours drawing, coloring, scribbling, as if I were reflecting without words, at the same time that I seek and work on the sounds that will later become music. Visual Music is the closest term I can find to define my creative process. It is my artistic being-here, which makes me passionately experience color and sound, without prejudice, without barriers, without limits. In a wild, but elegant freedom.

NUNO CÔRTE-REAL

BUILDING BRIDGES

Building bridges is probably what I would choose as the most emblematic feature of Nuno Côrte-Real’s music.

Bridges, first of all, between the contemporary composer and his audience, in the very opposite of Milton Babbitt’s infamous remark “who cares if they listen?”. Côrte-Real does care — and intensely so — if he is heard, and thus his music seeks to establish a strong emotional connection with his listeners, without ever compromising its authenticity or giving in to any easy solutions and clichés, but rather through a powerful lyrical drive that attracts us and involves us from the very first notes of each piece.

Bridges, also, between different—sometimes even remote—links in the chain of Western Music history, using freely the compositional techniques of various periods and schools, but merely as raw materials for an unequivocally contemporary approach as a composer. Consonance and dissonance, as well as tonal organization and atonality, are thus handled outside any specific historic context and free from any evolutionist notion, creating a flowing sequence of light and darkness, tension and release, density and transparency, roughness and delicacy. In a recent album, for instance, he has gone back to the Elizabethan period to establish a creative dialogue with the songs of the greatest of all English Mannerist composers, John Dowland (“Time Stands Still”, 2021).

Bridges, still, between the various musical genres, refusing any hierarchy between highbrow and lowbrow composition, and exploring instead the possibilities of intercommunication between the so-called “art music”, traditional rural songs and dances, and urban popular music of various periods. It is not a “cross-over” in the usual sense of the expression, which tends to signify an appropriation of one specific musical language by another, depriving the former of its own nature and submitting it entirely to the rules and presumptions of the latter. It is, in fact, as if the two genres are invited to find a common ground, establishing a new, shared territory, which no longer abides by the norms of either of its predecessors but is, nevertheless, highly coherent on its own terms. Côrte-Real has done so with old nursery rhymes (“Lagarto Pintado”, 2019), with traditional popular chant and polyphony from the Southern Portuguese province of Alentejo (“Cante”, 2019) or with Jazz (“Agora Muda Tudo”, 2020).

Bridges, finally, between words and music. In a substantial production of vocal music (including three operas – “A Montanha”, “O Rapaz de Bronze” and “Banksters” – and numerous songs and song cycles) he clearly demonstrates a keen understanding of poetry, both in terms of its expressive meaning and with regard to the intrinsic musicality of the words themselves. Not, however, by making a literal transposition of the text’s prosody into the music, but rather by finding a constant balance between the strict respect for the poem and the autonomous consistency of the musical discourse.

RUI VIEIRA NERY

Instituto de Etnomusicologia – Centro de Estudos de Música e Dança