XAVIER LOUREDA

ICONOGRAPHY OF LISTENING

XAVIER LOUREDA

Painter

Xavier Loureda (alias of the famous Portuguese composer and conductor, Nuno Côrte-Real), is a concrete painter dedicated to abstraction, both in a geometric and non-geometric world.

But beyond that, Xavier Loureda exists as a true heteronym, a real person inside the men’s spirit, and like the example of the multiples persons in the work of the poet Fernando Pessoa, it is the painter who materializes the sound of the musician into colour and form.

Each one of his paintings is the skin of music, the visual body of each note and silence, the movement of harmony, like a polyphonic architecture, the visible of music’s invisibility: it is a real and original iconography of listening. The high sounds and those low and deep, the tones and notes, becomes seen to the eye, free from the pentagram and alive in a world of chromatic intensity and dynamics.

“Loureda, taking a different path from the one of Klee’s – and here relies his unique and absolute particularity – doesn’t translate literally a written score, does not interpret a pentagram into a pictorial mean: the artist creates the images, the pure forms, before writing his own music. He sees it before being articulated into the world of notes and rhythms and tones. And what is, in reality, this singular way of seeing, but rather imagine the music to come, an interior vision which becomes matter in the outside, subjective and communicable like the sound it self? The law of Loureda is geometry. Colour is his freedom. Music is everything: soul, origin, and path.”

The artist works with several techniques and styles, including pastel and acrylic, on paper and canvas, and explores often the inclusion of matter in his paintings, like sand, screws, books, pencils, and others. He has exhibited his work on several occasions, in Milan, London and Paris, and worked with the famous Italian art marchand, Jean Blanchaert.

1.LABIRINTOS

2.LABIRINTOS

3.LABIRINTOS

4.LABIRINTOS

5.LABIRINTOS

Listening to the images

Works by Xavier Loureda

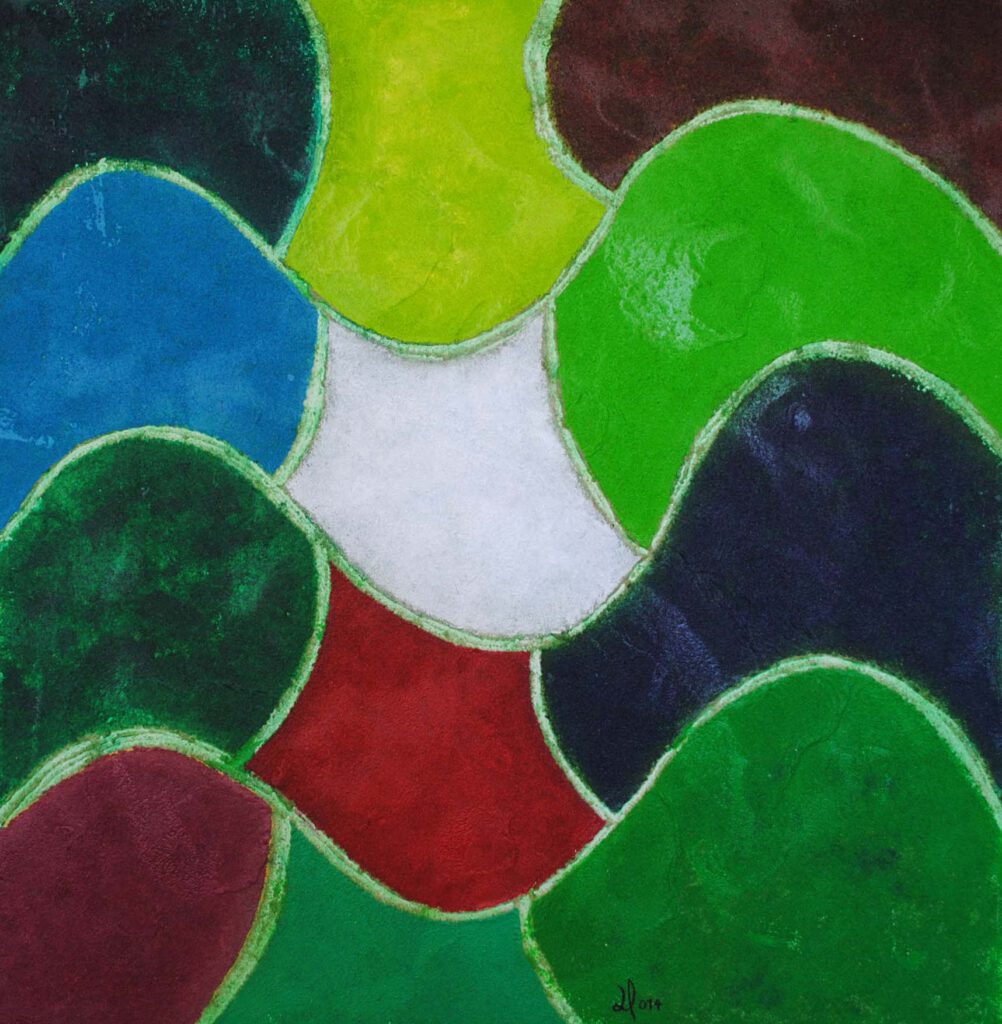

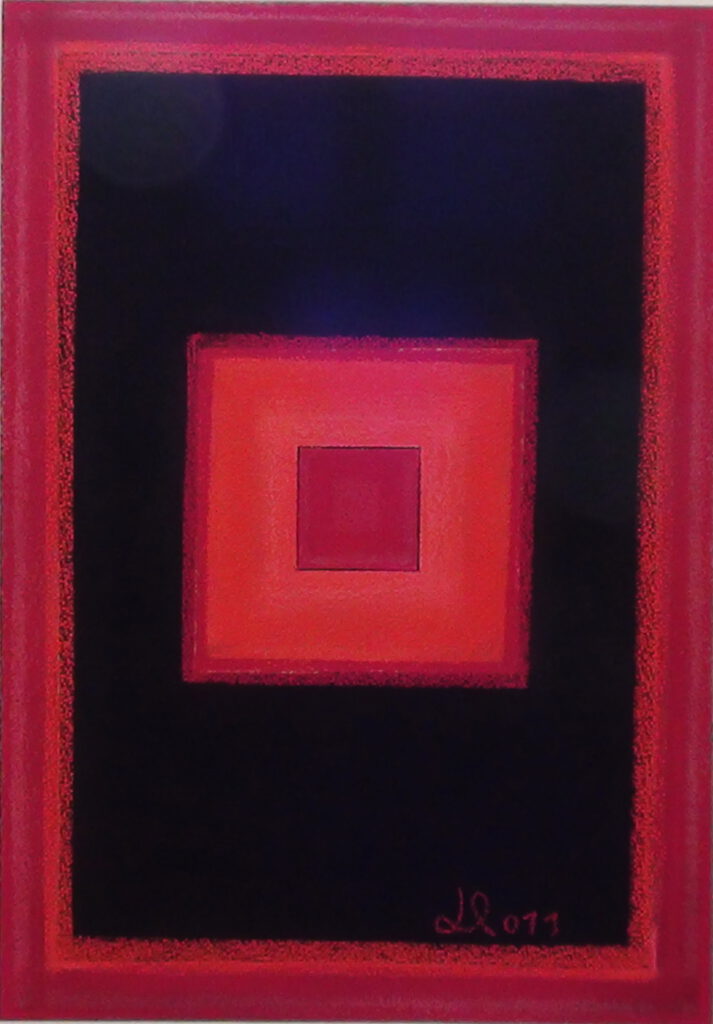

From the antimatter of an absolute black placenta, a clear, orange shape emerges, enclosing a heart of lava portioned by a thin black casket: the square line that, starting from the periphery of the image, returns to cut the center, to delimit, to order with clarity an otherwise explosive chaos. The energy that derives from it and that is perceived without hesitation consists precisely in this, in containing and channeling the force of color in a form that holds and contains. (Quadrado vermelho sobre fundo preto).

Strength is not exalted in dissipation, but in concentration, in respecting proportions. The flat and solid geometry, which could appear as the most cold of expressive forms, instead plays with Loureda as a precious ally, even when it alternates with small chromatic thickenings without edges, indulgent towards a composed fluidity, which expertly obscures a yellow edge with cobalt, revealing the birth of a gem-like green, modest and brilliant (Composição simétrica, IV).

A colorful chessboard full of turquoise, mauve, canary yellow and ochre, cerulean blue and Persian blue, cherry red, carmine and coral, is quickly crossed by two thickened and insistent chromatic tracks, one bistre, the other light orange and haloed with white as if leaving a trail (Linhas paralelas).

Broken and nervous segments invent a new alphabet, a new compositional syntax set between polygonal ruby gems, cutting the vertices so as not to obscure small milky skylights in a concentric and radiating circumference whose center is very difficult to find, enchanted by the centripetal force of the figures and by the centrifugal force of the luminous arrows that flow from the circumference at regular intervals (Círculo).

And again a suffused background, more airy and less dense, in the moment of the breath of the pastel yellow rarefaction seems to let delicate pulsating cells emerge, now magenta and raspberry, now aquamarine with a nucleus of a darker, coagulated tone. Immediately their evaporation is enclosed by a white, radiant halo, and a new cosmogony seems to have taken place in the planetary maps (Circunferências).

Xavier Loureda, alias of the established Portuguese composer and conductor, Nuno Côrte-Real, is a concrete painter dedicated to geometric abstraction. He prefers the use of pastel on paper, which frees the geometrization of forms from their natural coldness. Each of his paintings is the epidermis of music, the body of its notes and its silences, that of the movement of harmony, a retinal and architectural polyphony, the visible of that invisible that music has always represented: it is a true iconography of listening. The high and low sounds, the timbres and tones can be seen, freed from the pentagram cloaked in colors and a new cloak of visibility, the same that Paul Klee, also a musician as well as a painter, sought and wove pictorially throughout his life to dress his art.

Since the sixteenth century, the intertwining of music and visual arts has asserted itself with its virtuosic experiments. Just think of the perspective lute designed by Giuseppe Arcimboldi (known as Arcimboldo) at the court of Rudolf II in Prague, with the intention of translating colors into musical sounds. Passing through the ocular harpsichord of the Jesuit Father Castel two centuries later, we arrive at the luminous piano of the Russian composer Aleksandr Nikolayevich Skrjabin, who devised a correspondence table according to which a color was projected for each note during the performance of a piece. Epigonale are then Wassily Kandinskij, masterful visual interpreter of Ludwig Van Beethoven and Igor Stavinsky, and Paul Klee who lyrically inflamed Bach’s fugue in red (Fugue in Red, 1921).

Loureda however – here lies his absolute peculiarity – does not translate iconographically, does not figuratively interpret a score already written, does not transpose a pentagram onto a pictorial support. The artist creates images, aims at the definition of pure forms, before writing his own music. He sees it before it is articulated in his own composition of notes, expressed by the grammar of that alphabet that is not shared by any other word, neither prosaic nor poetic. He perceives it therefore, before it is there, at least on the page. And what is this particular seeing, if not imagining? What is this seeing if not an interior vision that becomes a fact of the world, intersubjective and communicable like sound?

In Imagination: Ideas for a Theory of Emotions, J. P. Sartre acutely identifies the status of imagination in an act of freedom that is foundational and denoting of the human being, in that it allows us to place in a (mental) elsewhere what is denied in its presence in the world. Man is always concretely immersed with his body in a given situation, in a precise space-time reality, and yet he is equally free to detach himself from it with an act of consciousness that denies that part of the world and gives birth to something in another place.

The musical composition that is not written on the stave, that is not played by musicians, is neither audible nor legible: it is not there. And yet it is there, in an elsewhere. It already exists in its sonic and traditionally graphic absence. That is, it dribbles the denial of its presence guaranteed by the normal parameters of recognizability (the writing and reading of notes or listening to sound) to constitute itself first mentally, and almost simultaneously in the form of clear and distinct images, dense with color. This is conceiving music in image, but in a primordial way.

Far from its weakest identification with the inconsistency of things, imagination and vision are here a bright and joyful example of how they are capable of the most difficult genesis: that of giving a body to music, a chromatic and mellow body, vibrant and austere, made of milky ways and galaxies as in every microcosm that has been able to give the cosmos rules and diagonal limits, segments, circumferences, squares, maps of enchanted freshness to see the invisible, of severe, thoughtful compositional rigor.

This is what Johann Wolfgang Goethe wrote about invention and rigor: This is the path of all kinds of creation: In vain will the unbridled spirit try to reach the summit of perfection./Only self-discipline can lead to greatness./Accepting limits reveals the great master,/and only the law can give us freedom.

Loureda’s law is geometry. Color is his freedom. Music is everything: soul, origin, goal.

Cristina Muccioli

Art critic.

contact for informations, questions and orders:

xavierloureda@gmail.com